OPINION

RHC closures may just erode care, not free up care resources

The prospective closure of state-run residential habilitation centers (RHCs) serving those with severe disabilities has been a contentious issue for years. It’s been subject to innumerable studies, with a new one tasked to begin by Sept. 1.

In the past session, the Legislature, in 2SSB 5459, agreed to close two RHCs. Bremerton’s Frances Haddon Morgan Children’s Center will close outright by Dec. 31, while the Yakima Valley School in Selah will close, through attrition, once its now-frozen population drops to 16.

Three facilities will remain.

While RHCs were characterized as schools, the new law bars admission of any resident under 16 — and allows for only the short-term care of those under 21 lacking alternatives. That arbitrary age limitation may or may not be legal.

Proponents of closure argue RHCs represent an antiquated, institutional model of care that the disabilities’ rights community has fought to move away from. There is no dispute this is how the RHCs started out.

Indeed, they represent a commitment as old as statehood itself. Article 13 of the Washington Constitution, as originally-worded in 1889, provided for the state to foster and support institutions “for the benefit of blind, deaf, dumb, or otherwise defective youth; for the insane or idiotic[.]”

The population of RHCs today is but a fraction of what it was once. However, RHCs have also evolved with the times.

In the 1999 Olmstead decision, the U.S. Supreme Court held that under the Americans with Disabilities Act a state is obligated to serve citizens with disabilities in the least-restrictive setting appropriate to care needs.

Writing for the Court, Justice Ginsburg rebuked “unwarranted assumptions” that persons with disabilities “are incapable or unworthy of participating in community life.” Yet the Court has also recognized not every person with disabilities can be served in a home-like setting. And inherent in any right of choice is the right to choose a care setting some may disapprove of — like a state-run institution. There are those who simply prefer the social setting, and accountability through many monitoring sets of eyes, of a facility.

We’ve moved away from the dark days when those with disabilities were “warehoused” in institutions. Washington has been ahead of the curve in developing community-based options for long-term care.

Yet huge need goes tragically unmet. Last month a KING-5 news story highlighted the fact that more than a third of those with disabilities are not receiving state assistance, and reported on one mother caring alone for a 24-year-old daughter — who had not been expected to live past age 9 — who is blind, deaf, and has severe mental and physical disabilities that give rise to behavioral issues. The mother had contemplated hanging herself.

For many of those desperate and without any state assistance, I know RHCs look like gold-plated oases. If they are closed, would not the money saved serve unmet community care needs? A House bill report summarizing testimony in support of 2SSB 5459 states, “savings would be used to provide services to the 13,600 on a waiting list.” Not necessarily.

First, from an economy-of-scale perspective, it may be for some with severe disabilities that RHC care is as efficient as care is going to get. For all its talk of “deinstitutionalization,” the state has offered private nursing homes enhanced rates to admit some RHC residents. However, a generally geriatric setting is not appropriate for a younger resident with behavioral issues. Nursing homes are limited to admitting residents fitting their care standards.

Nor would saved dollars necessarily follow residents. The Legislature doesn’t preserve such nexuses even where promised.

In the past several years the Medicaid census in private nursing homes has been reduced by thousands, and yet the state still cut service hours for in-home care clients by an average 10% this past session. Dollars saved from RHC closures are more apt to be diverted to spare the Legislature tough decisions on creating a more equitable tax system, for example, than they are to bring justice to those with disabilities awaiting respite in the community. Thus a RHC’s closure may only succeed in depriving its residents of quality care without bringing improvement to the lives of anyone else.

Indeed, the fiscal note for 2SSB 5459 quantifies the savings from two RHC closures as only being sufficient to fund a mobile treatment team and “two state-operated short-term crisis stabilization beds for adults and 3 beds for children, serving a total of 20 people in crisis per year” (the budget increased this to seven beds) — hardly a groundbreaking expansion of services for the unmet need of 13,600 residents. At the same time, further severe cuts were made in the state’s budget to employment and day services for those with disabilities.

Over half as much money could have been redirected toward care simply by closing a Lieutenant Governor’s Office essential to no one’s needs.

In short, it would be impossible to link any substantive improvement in the lives of those with disabilities to RHC closures. Were it possible, we could at least have a better argument.

Proponents of RHC closures have, at times, assailed those defending the institutions as being more interested in preserving union jobs than the welfare of residents.

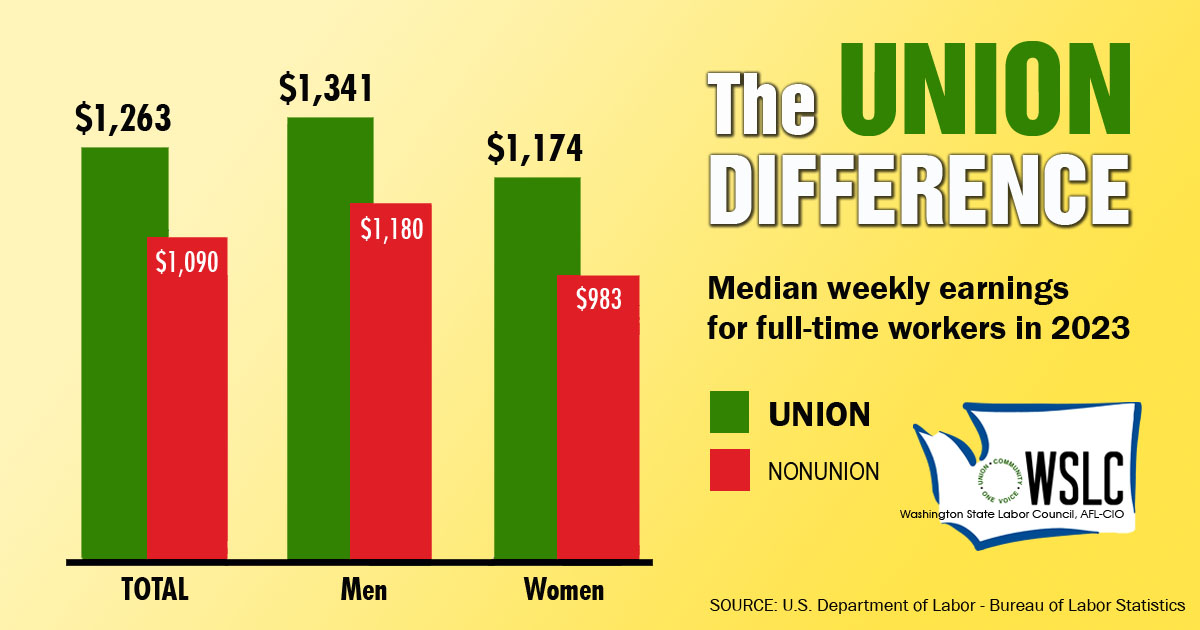

To be sure, workers in state-run institutions are paid living wages and benefits. What’s wrong with that? As the uncle of two nephews who received in-home care, I can think of nothing more important for the continuity, and quality, of care than living wages and benefits. I would much rather the care of my loved ones be well-funded than done on the cheap.

Voters in our state obviously agree. They have voted to allow home care workers to collectively bargain for wages and benefits, and also voted to mandate additional training and background checks for such workers (a mandate suspended by the Legislature).

If living wages are pitted against care, both will lose — an outcome likely to be fine with a Department of Social and Health Services run by one of Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker’s best friends and leading donors. So, instead of lowering the high standard of care RHCs represent for a small population, why not work together to raise it elsewhere?

A RHC may not be one’s ideal vision of home. Yet such facilities have been home to hundreds of Washingtonians. Their closure, and displacement of residents, will bring with it the sort of transfer trauma that’s been recognized in instances of long-term care facilities closing. We cannot be dismissive of those emotional consequences.

People with disabilities are not widgets that can be moved interchangeably from one RHC to a perhaps-distant care setting – they have emotional needs. Yet there was a veto, citing cost, of the new law’s requirement that the state facilitate “supports needed to assist family and friends in maintaining regular contact with” discharged residents. And I thought this was about residents’ best interests?

The RHC issue brings forth a tragic social Darwinism pitting against one another advocates for different groups of those with disabilities. I’ve had impassioned friends on both sides. It may be, with respect to the unassailable goal of preventing unnecessary institutionalization, we can declare victory and move forward — together. My hope is this is the outcome of the study 2SSB 5459 requires prior to any move to close the remaining RHCs.

Brendan Williams is a former State Representative from the 22nd Legislative District.