OPINION

America’s dark secret: Most can’t afford cost of end-of-life care

I visited two men in a local care facility yesterday, both in their 90s.

One of them still hopes to return to his home. I woke him, wheeled him to lunch and listened to him for an hour while he ate. Remarkable as his memory remains, I see it dimming from month to month, and I know he’ll never be able to go home again. At times he seems to know it, too. For him, as for millions of others, it’s the end of the line.

The other man is a few years younger, a disabled veteran of World War II. When he talks he seems coherent, the synapses behind his rheumy eyes still snapping brightly. It’s him saying something to someone who is not there, or grinning goofily at nothing at all that tells me he is surely slipping away from the rest of us. “Dwindling,” as a physician I know calls it.

But both are still with it enough to worry about money. They’re not sure how they’re paying for their keep, and they’re not sure who is. One wants to know what happened to the proceeds from the scrap metal his neighbor and caretaker sold for him. The other would like to get back the $350,000 he thinks a nephew took. To their money worries, I respond with generalities and do not tell either of them they are not paying the monthly rest home tab, because both are what my grandmother would have called wards of the state. They are proud men and could never have imagined such a thing happening to them.

But then all those who manage our economy didn’t imagine it either. The way we finance end-of-life care in the United States remains a deeper, darker secret than what Mitt Romney really believes about anything.

The numbers reveal a part of what’s happening to our parents and grandparents.

Currently, about 1.4 million of them are in long-term care. Their average age is 82. Once in residence, they are expected to live another one-and-a-half years. Sixty percent of those, like the two I visited yesterday, cannot pay the $5,000 to $7,000 monthly care costs, so Medicaid — that is, taxpayers — pay. Those payments add up to about $70 billion a year, almost the cost of a war. Of the 15 percent who can afford to pay for their care, three years in a nursing home will cost a cool quarter of a million. Because they can afford to pay their way, we call them the lucky ones.

The prospect beyond those simple statistics is even more disturbing. Until the Crash of 2008, our parents and grandparents lived in a world of economic expansion. Recessions aside, for them, it was mostly good times. But for average members of their cohort to pay for their long-term care, a couple would have had to put aside $2,000 dollars a month for 32 years, not likely when median household income was less than $50,000. That Medicaid currently pays 60 percent of nursing home care tells us how unlikely it was.

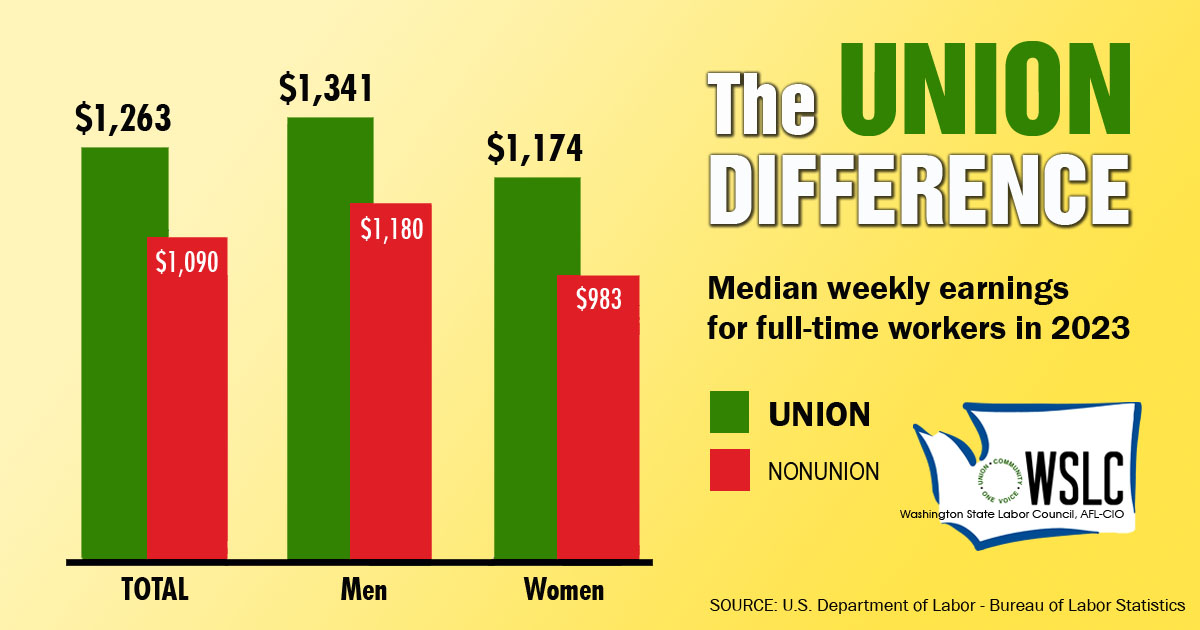

If the majority of our citizens can’t pay for their nursing home care now, what do falling wages — when the share of each dollar earned that goes to workers is the lowest since tracking began in 1947 — say about the future? The answer is obvious, and the Affordable Health Care Act did no more than gesture at the problem.

Our nation’s secret shame is more than those losing their homes, or the many who experience or fear hunger, or the panhandlers who emerge from under overpasses and out of tent cities to embarrass us on street corners. It’s the millions who are and who will be tucked away, dying, worrying about the money they don’t have, thinking that somehow they must have done something wrong.

That sad secret’s other face is the billions of taxpayer dollars already supporting our creaky end-of-life arrangements and bloating the profits of private care conglomerates that pay their workers only a minimum wage.

The two men I visit earned far more than their caretakers do, enough to support families and purchase homes. Not nearly enough, though, to retain those homes or their self-respect.

As end-of-life care costs increase and wages decline, the perfect storm of soaring costs and our aging population’s inability to pay them will only get worse.

And that storm has already arrived.

Jeff Winkes is a retired teacher and high school principal. He and Rich Austin have recorded a program on this subject, using the deaths and finances of our own mothers to illustrate the same point, for “We Do the Work,” a pro-labor radio program that airs in Northwest Washington. It is scheduled to air on Monday, June 4 at 5 p.m. at KSVR 91.7 FM in Skagit County, or you can listen to live streaming of the broadcast. It will be posted here the following week in the show’s archive of broadcasts.