OPINION

50 years ago in Memphis, a new phase of our movement began

The time is right and it is our moral duty to work together to fulfill Dr. King’s social and economic justice dream

By JEFF JOHNSON

(Feb. 2, 2018) — At the end of a blustery and rainy winter day two sanitation workers in Memphis, Tenn., Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed to death by a malfunctioning compactor in the garbage truck they were assigned to as it headed to the Shelby County dump.

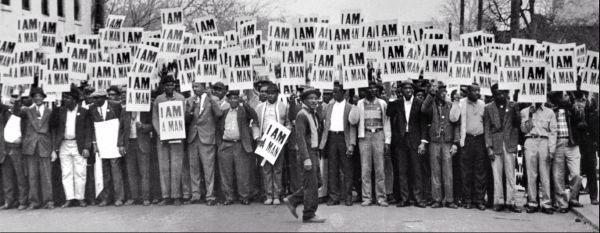

Fifty years ago yesterday, Feb. 1, 1968, this tragic and avoidable accident marked the beginning of a 65-day sanitation workers strike by AFSCME Local 1733 as 1,300 sanitation workers walked off the job in protest of poverty wages, inhumane working conditions, and the deaths of these two young men.

The rallying call for the strike became “I Am a Man.”

The picket signs didn’t outline a set of grievances, but rather the statement “I Am a Man,” which said it all — we are all human beings and we all deserve to be treated with dignity and respect.

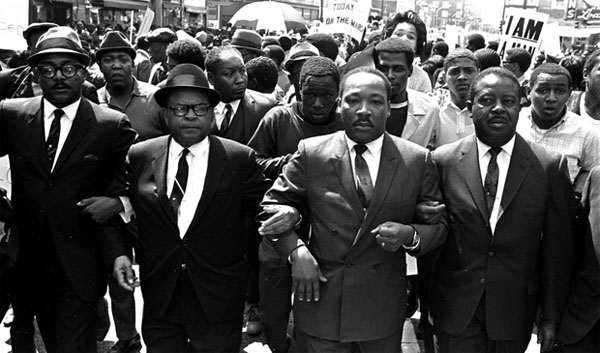

Dr. Martin Luther King, against the wishes of his staff, took a detour from his organizing around the Poor People’s Campaign to come to the assistance of the sanitation workers and the people of Memphis. He found such inspiration, hope, and unity in the sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis that it became emblematic of what the Poor People’s Campaign was all about:

“You are doing many things here in this struggle… You are demanding that this city will respect the dignity of labor… All labor has dignity… the person who picks up the garbage is as essential to the health of society as the physician.”

“You are reminding, not only Memphis, but you are reminding the nation that it is a crime for people to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages!”

“Do you know that most of the poor people of our country are working every day. And they are making wages so low that they cannot begin to function in the mainstream of the economic life of our nation.”

“You are here to demand that Memphis will see the poor”

“If America does not use her vast resources of wealth to end poverty and make it possible for all of God’s children to have the basic necessities of life, she too is going to hell.”

The new phase of the movement and struggle for freedom was to end racism, poverty and to end the Vietnam War.

Dr. King noted that “now our struggle is for genuine equality which means economic equality. For we know that it isn’t enough to integrate lunch counters. What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t earn enough money to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee?”

A complete restructuring of our economy is what Dr. King was talking about. More jobs, decent wages, union representation, affordable housing, and a guaranteed income was what was needed. And of course, that made Dr. King more dangerous to capitalism and the social order than ever before. All of this would cost money. All of this was about redistributing income and wealth. To top it off, he suggested that we not waste more money an unjustified and immoral war and use that money for constructive humanitarian purposes.

Of course, 50 years ago on April 4, as Dr. King returned to Memphis for a second march in support of the sanitation workers, he was slain by an assassin’s bullet while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel.

The true soul of America broke that day.

While the Poor People’s Campaign march that Dr. King planned still happened in June 1968 and the poor erected an encampment named “Resurrection City” on the National Mall, riots and civil unrest captured most of the news in the spring and summer of 1968, as solutions to the grinding reality of systemic racism and poverty seemed now to be on, what Dr. King had once referred to as, the “outskirts of hope.”

A couple weeks after Dr. King’s murder, the city of Memphis signed an agreement with ASCME Local 1733 which included a wage increase, grievance procedures, the right to join the union without fear of retaliation, non-discrimination language, the right to promotions to higher paying jobs, the right to deduct union dues from their checks and most importantly a recognition from the workers’ perspective that union membership was a basic right in America.

The victory in Memphis created an opening for AFSCME to organize tens of thousands of public employees throughout the south.

While the goals of the people’s campaign have yet to be fulfilled and the right, funded by the Koch brothers and other billionaires, has spent forty years building a network of organizations, communications networks, language, and policies to silence the voice of unions and people of color. Resistance and movement building has begun again through Black Lives Matter, Our Revolution, Indivisible, the Women’s March, the climate justice movement, and the new Poor People’s Campaign co-chaired by Rev. William Barber and Rev. Liz Theoharis (for more information go to www.poorpeoplescampaign.org).

The time is right and it is our moral duty to work together to fulfill Dr. King’s social and economic justice dream.

Note: Much of the thinking behind this piece was inspired by a forthcoming book by WW Norton & Company, To The Promised Land, by Michael K. Honey. Michael is our good friend who is a professor of ethnic, labor and gender studies at the University of Washington Tacoma. He has written a brilliant piece that traces the evolution of Dr. King’s thinking on economic and social justice. The book will be released on April 3, 2018. I suggest that you put an order in with your local bookstore, you will not be disappointed.

Note: Much of the thinking behind this piece was inspired by a forthcoming book by WW Norton & Company, To The Promised Land, by Michael K. Honey. Michael is our good friend who is a professor of ethnic, labor and gender studies at the University of Washington Tacoma. He has written a brilliant piece that traces the evolution of Dr. King’s thinking on economic and social justice. The book will be released on April 3, 2018. I suggest that you put an order in with your local bookstore, you will not be disappointed.

Jeff Johnson is President of the Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO, the largest labor organization in the Evergreen State, representing the interests of more than 600 local unions and 450,000 rank-and-file union members.

Jeff Johnson is President of the Washington State Labor Council, AFL-CIO, the largest labor organization in the Evergreen State, representing the interests of more than 600 local unions and 450,000 rank-and-file union members.