NATIONAL

The Janus v. AFSCME case: What it is, who’s behind it

The following article by Don McIntosh appears in the Northwest Labor Press:

WASHINGTON, D.C. (Feb. 15, 2018) — Less than two weeks from now — Feb. 26 — the U.S. Supreme Court will hear the most significant labor law case in decades.

WASHINGTON, D.C. (Feb. 15, 2018) — Less than two weeks from now — Feb. 26 — the U.S. Supreme Court will hear the most significant labor law case in decades.

In Janus v. AFSCME, a lawyer for an anti-union group will argue that requiring union-represented public employees to pay anything at all to the union would be an unconstitutional violation of their First Amendment free speech rights — because that would be like making them pay for political speech they might disagree with.

The court addressed that same argument more than 40 years ago in a 1977 case called Abood v. Detroit Board of Education and came up with a compromise: Union-represented workers who choose not to join the union don’t have to pay union dues, which pay for political expenses like lobbying, but they can, if state law allows it, be required to pay a lesser amount known as “fair share” fees — fees that cover just the union’s costs of negotiating contracts and representing members. Now, plaintiffs in the Janus case want the court to overturn the Abood decision based on the argument that everything a union does — even grievance handling — is political when the employer is a government.

JUDICIAL ACTIVISM: It’s no accident the Supreme Court is considering Janus v AFSCME. Unlike other courts, it chooses which cases it wants to hear. In a way, Janus originated in 2012, when Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito (pictured above) wrote the majority opinion in Knox v. SEIU, a case about refunds for workers who don’t want to pay for union political spending. Alito questioned the constitutionality of the Supreme Court’s 1977 Abood decision, which says it’s okay to require public employees to pay their fair share for union representation. His words tipped off anti-union lawyers that they could challenge Abood. In Harris vs. Quinn in 2014, they challenged fair share payments for home care workers in Illinois, but a 5-4 majority decided only that the workers weren’t true state employees. The next attempt was Friedrichs v CTA, which sped through the court system but deadlocked 4-4 after Antonin Scalia died in 2016. With Trump appointee Neil Gorsuch confirmed in 2017, a 5-4 conservative majority was restored. Alito may get his wish.

If a majority of the court agrees, it would result in an immediate financial hit to public sector unions in 23 states, including Oregon, Washington, and California. In effect, the court would be imposing the so-called “right to work” policy on state and local governments nationwide.

The Janus case began with Bruce Rauner, a private equity fund manager with a net worth estimated at close to a billion dollars. Rauner, a Republican, won the November 2014 election for governor of Illinois. One of his first acts in office was an executive order halting the collection of the fair share fees. In hopes of making that order legal, Rauner also filed suit in federal court arguing that the fair share requirement was unconstitutional. The judge ruled that Rauner had no standing to sue since he personally was not a union-represented worker — but the judge allowed the case to move forward by agreeing to remove Rauner as plaintiff and replacing him with an Illinois child support enforcement specialist named Mark Janus.

As an employee of the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services, Janus is represented by AFSCME Council 31. Janus, who makes $71,000 a year under the union contract, objects to paying $45 a month to the union — because it takes political positions he doesn’t support, including advocating more spending on state programs, and higher taxes to pay for it.

But this isn’t the story of one man’s courageous fight against “compulsory unionism.” Janus is merely a vehicle for a network of anti-union legal nonprofits that have been working to give a 5-4 conservative court majority a chance to deal a body blow to their hated political adversary: the labor movement.

Since the Supreme Court agreed last July to hear the Janus case, hundreds of organizations and prominent individuals have filed or signed onto 75 “amicus briefs” in the case. The briefs give a preview of the arguments the court is likely to hear.

The National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation will argue that the case is about free speech. But if Janus were about free speech, you’d expect the nation’s foremost defender of free speech to support it. Not so: The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) argued in an amicus brief that employee free speech is already protected under Abood because nonmembers don’t have to pay any union expenses for political speech. To rule that they can’t be obliged to pay for representation either would trample on another First Amendment right — freedom of association — because it would force union members to pay for nonmember services, the ACLU said:

“Even employees who favor the union’s positions or any benefits it conveys will have every incentive to shift the costs of their representation to members, as they will be able reap the same benefits without spending a dime. As the Internet has repeatedly shown, individuals who get something for free cannot be counted on to voluntarily pay for it.”

In other words, Janus isn’t about free speech; it’s about free riders.

Land of the free riders?

Imagine. You pull up to the gas pump, and get a choice: pay the sticker price, or skip out on paying the gas taxes and receive a 49 cent per gallon discount. And if you choose not to pay the gas taxes, you can still drive on the roads paid for by the taxes that other drivers paid.

Economists call this the “free rider” problem, and it’s at the core of the Janus case, because under the American system of labor law, democratically elected unions serve as workers’ “exclusive representatives,” and they have a legally binding duty to represent all workers in a bargaining unit, whether or not those workers choose to join the union.

Economists call this the “free rider” problem, and it’s at the core of the Janus case, because under the American system of labor law, democratically elected unions serve as workers’ “exclusive representatives,” and they have a legally binding duty to represent all workers in a bargaining unit, whether or not those workers choose to join the union.

Anti-union lawyers in the Janus case have argued that one way around the free rider problem would be to eliminate exclusive representation, and let dissenters fend for themselves. But exclusive representation has been a distinctive feature of American labor law since the 1926 Railway Labor Act, and it’s hard to see how it would be practical for state and local government employers to bargain separately with rival unions in a single workplace, or negotiate terms and conditions with tens of thousands of individual employees.

Some other key arguments against overturning Abood:

- Stare decisis — Stare decisis is Latin for “stand by things decided.” It’s a hugely important legal principle — the doctrine of precedent. If the court reverses its Abood decision, it invalidates 41 years of lower court decisions that relied on the Abood precedent, and it overturns laws in 23 states, affecting thousands of union contracts that cover millions of public employees.

- Federalism — Federal law is silent on whether state and local public employees have any collective-bargaining rights at all; it leaves states to make that decision themselves. That’s consistent with the Tenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which says that the powers not delegated to the federal government by the Constitution are reserved to the states. Today, 41 states give public employees at least some collective bargaining rights, and 23 plus Washington, D.C. have a fair share requirement.

- Consistency with other free speech rulings — The Supreme Court has long balanced the individual free speech rights of public employees against the prerogatives of public employers to run the workplace, and has given states wide latitude when they impose restrictions as an employer. The court has held that government employers can search employees’ desks without a warrant, question them about their backgrounds, require them to cut their hair, even bar them from participating in political campaigns after hours.

- Money isn’t speech — “This is not compelled speech. It’s a compelled payment of money.” That’s what a pair of prominent conservative legal scholars argued in one amicus brief. Seems obvious enough.

Follow the money

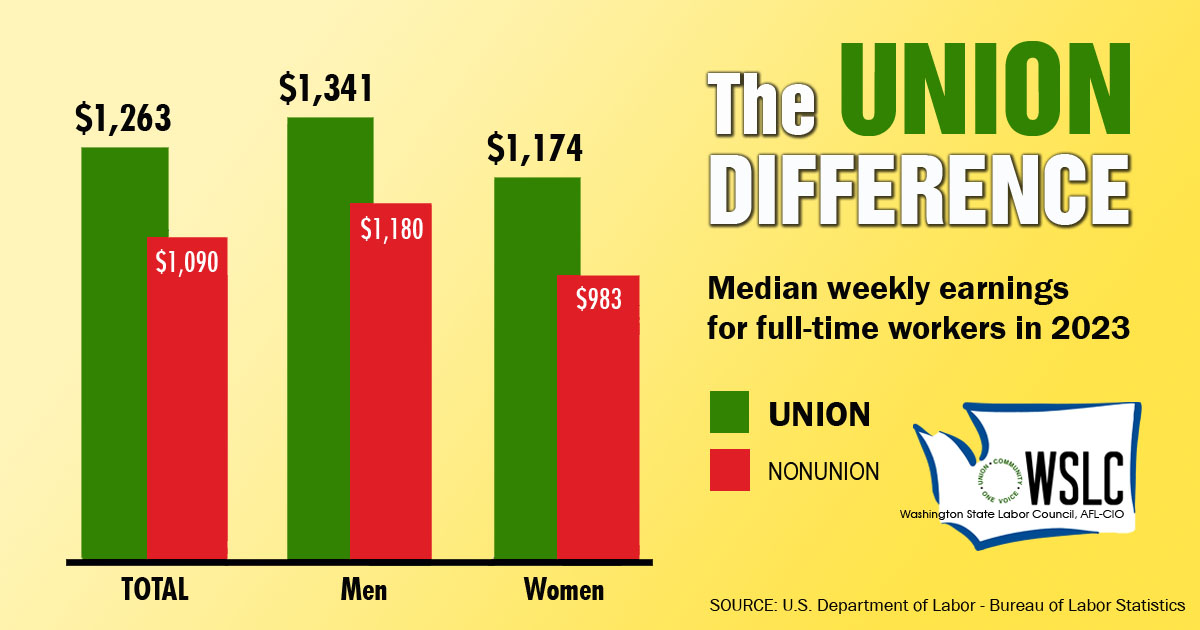

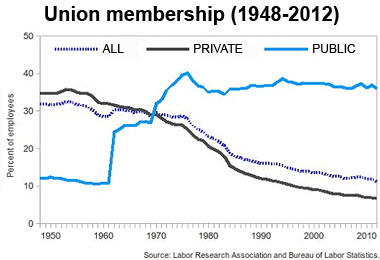

Janus needs to be understood in a much larger context. When public employee unions began to win the legal right to engage in collective bargaining 50 years ago, union members were 40 percent of the private sector workforce, and private sector workers had greater pay and benefits than public sector workers. That was 50 years ago.

Since then, public sector unions grew until they, too, represented about 40 percent of the public sector workforce, and the public sector caught up in wages and benefits. But during that same period, deregulation, offshoring, outsourcing and aggressive union-busting by employers reduced unions to 6 percent of the private sector workforce.

Since then, public sector unions grew until they, too, represented about 40 percent of the public sector workforce, and the public sector caught up in wages and benefits. But during that same period, deregulation, offshoring, outsourcing and aggressive union-busting by employers reduced unions to 6 percent of the private sector workforce.

Today, the public sector is in some ways the last stronghold of real union power: Maybe not enough power to call the shots, but enough to hang on a bit longer to the wages, benefits and job security that used to be the the standard — set by private sector unions — for every American worker. With the labor movement in overall decline, unions have turned increasingly to the public and try to win gains for workers through politics.

That’s why the list below of who’s filing all the anti-union amicus briefs is so telling: It’s a who’s who of think tanks and anti-union nonprofits funded by a network of politically active right-wing billionaires, led by the Koch brothers. The same groups contributed to the corporate-tax-cutting Republican takeover of Wisconsin, Michigan, and other states. They’ve engineered this moment, not because they care about the rights of union dissenters but because they’re determined to remove unions as obstacle to imposing a radical corporate ideology.

After questioning lawyers for both sides Feb. 26, the Supreme Court is expected to make a decision in the Janus case before its June recess.

Taking sides

As the labor movement gets ready for its “day in court,” it’s backed by 39 amicus briefs from church groups and a broad cross-section of civil society groups, all asking the court to reject Janus. Meanwhile, all but two of the 36 anti-union amicus briefs come from the same mostly-obscure network of anti-union think tanks and legal foundations funded by the Koch brothers and their ilk. [You can see all the briefs here.]

As the labor movement gets ready for its “day in court,” it’s backed by 39 amicus briefs from church groups and a broad cross-section of civil society groups, all asking the court to reject Janus. Meanwhile, all but two of the 36 anti-union amicus briefs come from the same mostly-obscure network of anti-union think tanks and legal foundations funded by the Koch brothers and their ilk. [You can see all the briefs here.]

Pro-union amicus briefs

- State attorneys general: Alaska, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Mexico, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and the District of Columbia

- Mayors: Los Angeles, Seattle, Chicago, New York, Philadelphia

- Faith groups: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA, Union for Reform Judaism, and dozens of others

- Civil society groups: American Civil Liberties Union, National Organization for Women, Southern Poverty Law Center, National Urban League, American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, Natural Resources Defense Council, Sierra Club, YWCA USA, Dēmos, Public Citizen, NARAL, Center for Reproductive Rights, Human Rights Campaign, Lambda Legal Defense Fund, National Center for Lesbian Rights, National LGBTQ Task Force, PFLAG, National Center for Transgender Equality, Union of Concerned Scientists, United Students Against Sweatshops, Jobs With Justice

Anti-union amicus briefs

- Trump Administration’s solicitor general

- State attorneys general: Michigan, Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

- Civil society group: National Federation of Independent Business

- Anti-union think tanks and legal foundations: 1851 Center for Constitutional Law, American Center for Law & Justice, Atlantic Legal Foundation, Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, Buckeye Institute for Public Policy Solutions, Cato Institute, Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence, Center on National Labor Policy, Competitive Enterprise Institute, Empire Center for Public Policy, Fairness Center, Freedom Foundation, Goldwater Institute, James Madison Center for Free Speech, James Madison Institute, Landmark Legal Foundation, Mackinac Center for Public Policy, Pacific Legal Foundation, Pioneer Institute, Rutherford Institute, Southeastern Legal Foundation