STATE GOVERNMENT

The Strippers’ Bill of Rights, one year later

This story was published in partnership with RANGE Media, Spokane’s independent, worker-owned press for the people. Sign up for RANGE’s newsletter here.

As club owners use a loophole in legislation intended to protect dancers, strippers are finding their own ways to fight back through labor organizing and pop-up shows where they keep all their profits

(June 5, 2025) — When the Strippers’ Bill of Rights was signed into law by then-Governor Jay Inslee just over a year ago, dancers across the state felt swells of hope.

“I was so happy, I cried,” said Kasper, a dancer based out of Seattle.

The Strippers’ Bill of Rights was a law championed statewide by the dancer-led organizing group Strippers Are Workers and designed to codify worker protections for dancers in Washington, where state laws uniquely endangered them. Among those laws is a ban on alcohol in clubs, which incentivized club owners to make the majority of their money by charging dancers predatory fees and back-rent — a practice that could leave dancers indebted to the club they danced at.

By all accounts, the bill’s passage was a victory for Washington strippers, who are frequently left out of labor rights conversations while facing an unfriendly economic landscape — one of the worst in the nation for strippers.

“I couldn’t stop smiling. It felt like such a big win,” said River Dreaming, a dancer and who organized with SAW to lobby for the bill. “Washington is such a generally liberal state that it’s been so weird that we had the most draconian strip club laws in the entire country. … It was just very heartening to have the bill finally go through.”

Original photos by Forest Gremlin, Art treatment by Valerie Osier

All that was left was to wait for its implementation, taking full effect until January 1 of this year, which would prohibit those predatory back-rent practices, cap the stage fees clubs could charge dancers at $150 a shift or 30% of the dancer’s earnings for each shift, whichever is less, and create a pathway for clubs to apply for liquor permits, allowing them to add a revenue stream that didn’t rely on charging dancers.

When the bill passed, it was “everything we hoped for,” Madison Zack-Wu, SAW’s campaign manager, told RANGE last year. But one year after Inslee signed it into law, dancers say conditions have changed — but in most cases, not for the better, as club owners have found loopholes they can use to maximize their profits at the expense of dancers.

The ‘revenue sharing’ loophole

Clubs don’t pay strippers to perform in Washington.

Instead, dancers are independent contractors. Similar to how tattoo artists might rent booth space from a tattoo parlor, or hair stylists rent a chair from a salon, dancers pay the club to use the stage, plus give a cut of their earnings from non-stage services like private or VIP dances.

Before the Strippers’ Bill of Rights went into effect, clubs had no limits on the cuts or fees they could collect. Dancers could work a full shift and leave with nothing, or worse: owing money to the club for stage fees they didn’t recoup in tips.

The new law was intended to ensure more money for strippers’ services ends up in their g-strings — instead of club owners’ pockets — by capping the amount of “stage fees,” clubs could charge dancers.

But club owners found ways around that.

Some clubs, like the Deja Vu Showgirls chain in the Seattle area, changed their profit models just prior to the bill’s implementation.

Instead of allowing dancers to conduct their business with customers as independent contractors and charging them the fees that were capped by the bill at $150 or 30% of their income, some club owners stopped charging fees at all. Now, those clubs collect the revenue directly from customers and pay the dancers at the end of the night in a model club owners call “revenue sharing.”

Since they aren’t technically charging the dancers fees, this loophole lets club owners keep as much of the revenue from dancers’ labor as they want, all without being in violation of the law.

“Clubs are doing the things that clubs do, which is trying to have as much power over dancers as possible, trying to profit off the dancers as much as possible,” Zack-Wu said. “That’s the reason why we had to pass the bill in the first place, so it’s definitely no surprise there that clubs are still acting like clubs.”

The new model also throws a kink in dancers’ usual flow. Normally, if they’re giving a customer a lap dance, or a private service, they’re working to establish a rapport and a vibe, hoping the client will book more lap dances. Under the auspices of “revenue sharing,” customers have to leave the room and pay for each lap dance up front, instead of letting dancers “stack dances,” and settle up afterwards.

“It’s harder to sell more dances, which means dancers make less money and clubs make less money,” Zack-Wu said.

To her, this reeks of club owners caring more about establishing control over dancers, than just their bottom lines.

At least ten dancers in the Seattle area have filed complaints to the Labors and Industries board (L&I) about this new model. So far, the state has ruled in favor of the club owners.

If that pattern continues, dancers’ options are limited to legislative appeal or other methods of negotiating with clubs, like collective bargaining, Zack-Wu said. Still, she’s optimistic that L&I might respond differently to a new wave of complaints, eventually moving to close the loophole.

“ Implementation does not always go 100% perfectly at first, and I think we’re very much experiencing that,” Zack-Wu said. “We’re in that transitional phase of finding what works in the bill and finding what doesn’t, [finding] what clubs are exploiting.”

‘Imagine if an article about Starbucks doing this came out.’

The implementation of the revenue sharing model isn’t the only way that club owners have come down on dancers since the bill passed. For Kasper, who dances at Kittens Cabaret in Seattle, Zack-Wu’s comments about club owners trying to keep control rang true. When she went in to sign her annual contract in 2025, she found Frank Colacurcio Jr., a consultant at the club, at Kittens sitting in her meeting with a manager.

She recalled him saying: “‘Why do you think this bill passed? Do you think this is, like, actually gonna be good for the club? Why do you think this bill passed? Do you think this is like actually gonna be good for the club? You know, we’re gonna have to charge you more, ‘cause now we have to pay the city more.’”

(There is no language in the bill that indicates why he would have to pay the city more.)

She felt like he was trying to intimidate her; she had been active in SAW and educating her fellow dancers about their rights.

Colacurcio Jr. is banned from running strip clubs in Washington, but still has a hand in Kittens Cabaret as a consultant (though dancers allege he is the de facto owner.) His dad has also garnered a reputation as the strip club “mob boss” of Seattle that’s so infamous that he has a musical written about him.

Colacurcio Jr. told RANGE that he shares an office with the manager. We read him the questions Kasper remembers him asking, and he said he didn’t “say anything like that. The most I might have asked them is how they felt about [the bill].”

He had his own feelings on the bill: “I love the safety measures. I felt that was important.”

But, since the bill went fully into implementation, the club’s costs have increased, with payroll up by $5,000, which Colacurcio Jr. says is due to increased labor costs after staffing up security to meet provisions in the bill.

2025 has also been less profitable for Kittens than years’ past, in a big way. “No profit at this point in time,” Colacurcio Jr. told RANGE on May 16. “ My opinion that I gave the owners was, if they can’t make a profit by the end of the year, I would shut the place down, personally.”

He didn’t solely chalk it up to the bill; he also pointed to economic insecurity from Trump’s tariffs (a trend that sex workers have noticed nationally) and drastic increases in rent costs.

While the bill set caps on how much clubs could charge dancers for their services, it didn’t put a cap on how much the property owners — who in some cases are different than the club owners — could charge in rent.

“If the bill said, landlords can’t raise rent, it would’ve been wonderful, because that would have given us a little bit more stability,” Colacurcio Jr. said. “But you only have two revenues: the dancers and the customers. If you take too much from the customers, they don’t spend on the dancers and if you take too much from the dancers, they don’t work for you and there’s no customers.”

Two years ago, Kittens’ rent increased by about 45%, Colacurcio Jr. said. “The crying shame is that property owners know that the zoning’s so limited on these clubs that they can charge whatever they want and so they bleed you dry.”

Unlike Deja Vu Showgirls, Kittens stuck with the traditional profit model. Clubs that did shift to “revenue sharing” are “within their rights to do that,” said Ben Dimaano, one of the part-owners at Kittens, “But we’re not like that.”

He’s heard from dancers they don’t want that model, and from customers that it ruins the “allure,” to have to pay for things upfront, so they’ve continued to charge dancers the stage fees.

“ The customers are more of the dancer’s customers, but always treat the dancers like your customer,” Colacurcio Jr. added.

Though Kittens stuck with the traditional profit model, following the 30% fee cap, Kasper said, they “became way more controlling in other ways, like trying to police what we wear, telling us what to do on stage, telling us how much we can charge for our dances … just sneaky little ways to find control anywhere that they can.”

Dimaano confirmed that the club had changed policies on prices, setting a minimum price of $40 that dancers had to charge for lap dances. They also take the maximum allowed by the law, $150, during prime shifts, like weekend evenings, but have a discounted fee at less busy times of the day.

Madison Keevy, who also danced at Kittens, had different issues with management. Keevy had been dancing in Washington since 2017, taking to the career quickly because it worked well with her schedule and her disability. She took a break during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, but decided to come back to the stage after the Strippers’ Bill of Rights passed, hoping for an accessible workplace with better labor protections.

But when she started back up at Kittens, Keevy told the Seattle Times she made less than she had before the rules went into place, and perhaps worse: medical accommodations she requested were ignored, resulting in strobe lights repeatedly being played while Keevy was performing.

Kasper confirmed the story: Kittens used strobe lights during one of Keevy’s performances, despite knowing it was unsafe for Keevy to dance under them.

Dimaano said that the issue with the strobe lights was an “innocent mistake.” He said that Keevy had only notified the DJ, who controls the lights during performances, and not management. If Keevy had notified management, they would have notified the DJ.

“ We felt really bad, were really apologetic, the DJ was apologetic,” Dimaano said. “ This happened on a busy, busy Friday night and it was an innocent mistake, and then she just kind of got really upset, like angry.”

Keevy said it wasn’t an innocent mistake, because she had disclosed it when she was hired, and it had happened two other times before. After the third time, Keevy tried to dance again and was told she needed to send management medical documentation before she could return.

Texts between Keevy, who uses the name Winona when she dances, and Dimaano, provided by Keevy.

Keevy shared with RANGE the emails she sent notifying management of her condition. Management at the club told Keevy in an email that they had sent her private medical note to “all management and staff members,” instead of just the people who needed to know to prevent strobes being played, like the DJ, which Keevy said violated her medical privacy.

Dimaano said that Keevy quit because she didn’t want to come in for an in-person meeting with management — citing fears that there would be strobe lights playing in the club. Keevy said this isn’t true.

“I never said I didn’t want to go in because of the strobe light. Obviously I was able to work there for an entire month so that makes no sense,” she said. “The reason I did not go in is because they wouldn’t allow me (to have) a third person to be present.”

An email to Keevy from the “Kittens Cabaret” email address started with, “We are sorry to hear that you verbally informed us that you do not want to conduct your business with us anymore,” but states she was “never terminated,” just told she needed to come to the office since the office “handles medical.”

Keevy maintains that she’d disclosed her condition upon employment and tried to meet with management, but was told that it needed to be with Dimaano, not just floor managers, and happen during a shift she does not work and has other commitments.

She also wasn’t comfortable meeting with Dimaano alone, who she said was aware of her condition and ignored it: the second time strobes were used while she was dancing, Keevy gave him data from her Apple Watch showing that her heart rate was elevated from the strobe usage. He brushed it off, she said.

Keevy said she was essentially terminated, because management refused to let her return to work, even after she’d jumped through hoops: providing her doctor’s note and coming back to the club in person. She no longer dances at Kittens and is seeking other employment.

Though Kasper has continued to dance at Kittens, she said the vibe has changed since the bill’s implementation, starting with that initial meeting with Colacurcio Jr.

“ The lower down managers are being kind about [the bill’s implementation], but the owners are being scary,” Kasper said. “Imagine if an article about Starbucks doing this came out,” she said.

And her bottom line is taking a hit too: customers are spending less, and dancers think it’s because they can sense the tension between dancers and managers.

“They can tell something’s going on behind the scenes,” Kasper said. “The managers don’t wanna help us make money. We don’t wanna make them money, we’re butting heads and it’s ruining the money for everyone.”

Kasper said she’s making 50% or less than what she was making in 2024, and has had more “$0 nights,” where she’s left the club making no income, than she’s had in her whole career.

“It feels terrible because I chose this job to work for myself, instead of some major corporation, and I will go to work and I’ll work my ass off and my feet hurt ’cause I’m wearing huge heels and my arms hurt from pulling myself up on the pole and I have nothing to show for it,” she said.

Editor’s Note: We have updated this section to reflect comments from Frank Colacurcio Jr. and Ben Dimaano.

‘The energy is just palpably dry.”

While dancers like Keevy took the bill’s passage as a positive sign to jump back onstage here, other dancers were more skeptical.

Since the closure of Spokane’s Deja Vu Showgirls in the fall of 2023, Ashe Ryder — a Spokane-based dancer and SAW advocate — has been competing in stripper competitions and travel-dancing, mostly at clubs in Wisconsin and South Dakota. But this summer, she wants to look for work closer to home.

“I’m really tired of flying places and the travel woes and being stuck in an airport for hours on end,” Ryder said. Still, despite making her home here, dancing in Washington doesn’t feel like the most economically viable option.

Because of restrictive zoning laws, no new clubs have opened to replace Deja Vu Showgirls, which was the last strip club in Eastern Washington. Ryder could travel to Seattle, which is a much closer drive, and perform at clubs there, but the King County license fee for strippers is $170 annually — much more than the $35 Spokane fee.

And, Ryder said, she’s heard from friends in the industry that the club environment in Seattle is “tense,” because of hostility from club management towards dancers and organizers. She went to check it out herself, popping into a club in Seattle as a customer, and it was dead, she said. “I think people don’t want to be at the Seattle strip clubs because you walk in and the energy is just palpably dry.”

Ryder, who is also involved in organizing with SAW, worries that besides the stage fee loophole, the law had other unintended consequences. While the law created a way for clubs to earn income through liquor licenses instead of dancer labor, Ryder thinks that club owners now just choose to double-dip. “They’re so used to taking and taking from dancers that now they’re like ‘oh, well, now we can serve alcohol *and* take as much as we want from the dancers.”

Because of what she’s seen and heard of the Washington stripping landscape, Ryder has to make alternate plans. Opening her own club here in Spokane is still her “biggest dream,” — she’s always scrolling commercial real estate and looking downtown for areas with foot traffic — but the zoning laws still make it an unrealistic goal for her right now. Until things change and that dream can become a reality, she’s hoping to dance at Stateline, a strip club just across the state border in Idaho.

‘Cutting out the middleman’

Like Ryder, River Dreaming is a Washington-based stripper who primarily dances out-of-state. Also like Ryder, Dreaming considered making a comeback to the Seattle scene, but after scouting potential clubs, they were unimpressed.

Instead of dancing out of venues belonging to predatory club owners, Dreaming, who is an organizer with SAW, has found a different way to make the most of the new state laws: by producing their own shows in nightlife venues.

Now that it’s legal for venues to have nudity and alcohol in the same place, bars are more open to hosting stripper shows, Dreaming said. “It provides the strip club experience, but cutting out the middleman of the club owners who are well known for being pretty shady and shitty and taking a big percentage of dancers’ income.”

At the shows Dreaming produces, dancers get paid $100 each out of ticket sales and average between $150 and $250 in tips. For a single stage set, with no lap dances, dancers can come away making between $250 and $350.

“For a lot of Washington dancers, that is a decent or good night working at the strip club, but you’d have to give a lot of lap dances and give quite a bit of money to the club in order to make that much,” Dreaming said.

They were inspired to create spaces that paid dancers fairly, and felt welcoming and safe for women and queer people. So far, Dreaming has produced three shows under the banner Skyclad Studio, including a show called “$apphic $pring,” last week at WILDROSE — the oldest lesbian bar in the United States and the only lesbian bar in Seattle.

The show sold out, with 15% of ticket profits going to benefit SAW, Dreaming said, and was a massive success.

“ What I heard from the other dancers was that it was very healing for them to be in an environment that celebrated their queerness and their sex worker identity at the same time, because so many strippers are queer,” they said. “In my experience, I feel like at least half of the strippers at any club that I’m working at are queer and we often have to hide that to do our job in clubs where the clientele is predominantly men.”

“It felt really good for everybody to be able to just unapologetically express that and get paid and tipped and cheered and adored for those parts of ourselves that we sometimes have to hide or downplay,” Dreaming said.

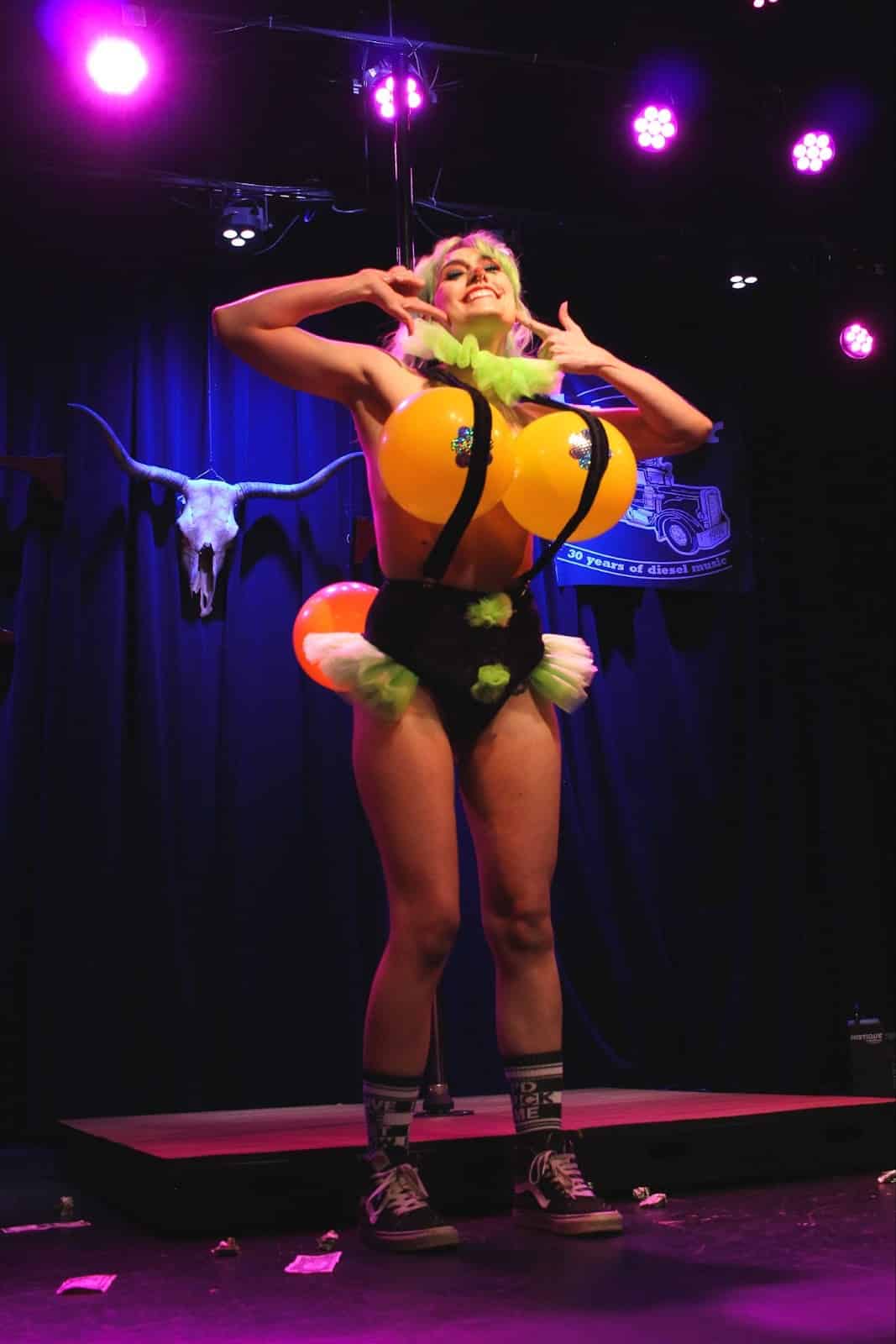

Ryder performing as a clown in a fundraiser show for SAW at the Tractor Tavern. (Photo taken by Dreaming, provided courtesy of Ryder.)

With a few successes under their belt, Dreaming is dreaming even bigger. They want to produce shows at even bigger venues. They want to produce fully nude strip shows, which could result in more tips, as well as help set strippers apart from pole fitness dancers and pole hobbyists.

“There’s been an issue with hobby pole performers taking up performance spaces and attention and money in the economy for pole shows, and a lot of those people are not gonna be comfortable doing a full nude show, whereas strippers like myself, we’re completely used to that. We’re happy to do it,” Dreaming said. “A big part of pole dancing from the stripper tradition is using your full nude body as a part of the performance to get more tips. So many pole spins that come from the strip club are about showing off…to the audience.”

Dreaming’s production model impressed Ryder, whose only Washington dance experience in the last year was at a stripper show at a non-traditional venue in Seattle.

“I think that’s a really cool approach too,” Ryder said. “These fucking club owners are bleeding us dry, so we’ll do our own thing.”

‘Out of the underground’

The initial implementation of the Strippers Bill of Right might not have gone according to plan, but dancers across the state are continuing to fight in their own ways: Ryder performed in a fundraiser show at the Tractor Tavern in Ballard to raise funds for SAW, Keevy is lobbying publicly for strippers’ rights and using her platform to write stories from her intersectional perspective and provide guidance to other dancers on navigating the field with a disability, Kasper is continuing to inform her colleagues of their rights and Dreaming is creating their own safe spaces for dancers to perform.

SAW is going to “keep holding the line against a lot of the criminalizing policy that’s been coming out against sex workers, like Seattle’s Stay Out of Areas of Prostitution (SOAP),” Zack-Wu said.

And, they just got a grant to do “Know Your Rights” trainings for strippers, which is going to be their focus for the future, Zack Wu said: “Making sure that everyone is educated on their rights and know how to file claims and making sure that in this implementation phase, we are getting all the information we can on how to make the bill work for dancers as intended.”

Keevy, Kasper and Zack-Wu all want to see the government step up to ensure the law is protecting dancers as intended, whether that’s with stripper-led audits of clubs, surprise visits from city inspectors to ensure clubs are following regulations, legislators moving to close the loophole that allowed club owners to pivot to the “revenue sharing,” model or complete decriminalization of sex work across the state.

Both Ryder and Dreaming long for a day when zoning laws, which are prohibitively restrictive in both Seattle and Spokane County, change for the better. If the old guard of club owners won’t sell the locations that are currently zoned for strip clubs to dancers, the law would have to change to allow new clubs to open.

Dreaming would love to see a club that is unionized or collectively-owned by dancers.

“If there was an environment like that, I think that it would be a huge hit in the general nightlife community,” Dreaming said. “It would feel like we’re able to come out of the underground where we’re all trying to thrive, but having a hard time.”