OPINION

Lawmakers should choose voters over donors on ‘free trade’

As a political scientist, I’m sometimes asked how it’s possible for a democracy to enact laws that are opposed by the majority of voters.

There is no clearer illustration of how this works than the current race to enact a free trade agreement with Colombia.

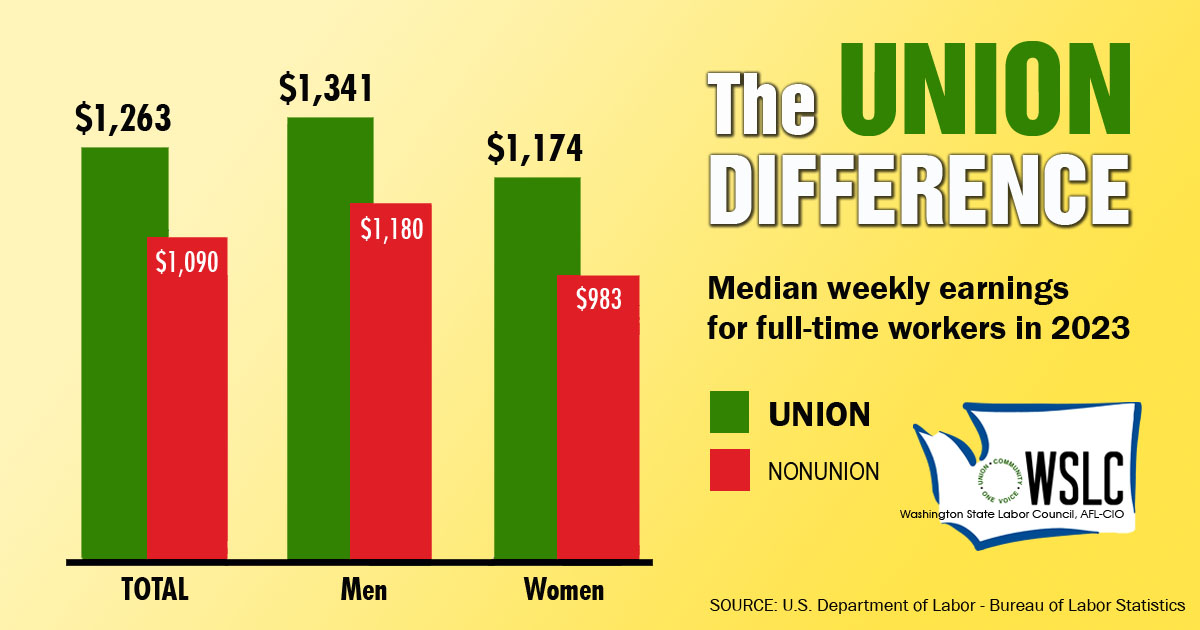

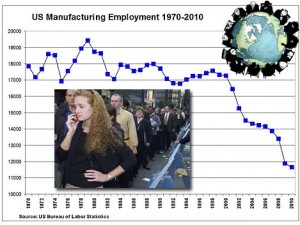

The majority of Americans opposes NAFTA-style treaties. It’s not just union members; only 27 percent of Republicans think “free trade” helps us. And no wonder: We’ve lost almost 5 million jobs since NAFTA was passed — many of them well-paying manufacturing jobs that were the backbone of the middle class. Millions of families have watched loved ones put out of work by companies who could make more profit in Mexico or China, leaving the public firmly opposed to such deals.

The minority that supports the NAFTA model, however, includes the country’s most powerful corporate lobbies. The strongest advocates of “free trade” are the Chamber of Commerce and multinational corporations such as GE, which sent tens of thousands of jobs overseas and built a profitable business helping others do likewise.

It’s particularly striking to watch Republicans on this issue. John Boehner is portrayed as captive to the Tea Party — but Tea Partiers are more opposed to NAFTA-style treaties than any other group of voters. Yet on this issue, their voices are ignored. When there is a conflict between the passions of their base and the dictates of their funders, Boehner and gang come down squarely on the side of the latter.

Republicans are famous for message discipline, but what’s remarkable right now is the lockstep silence on this issue. From Palin to Boehner to Fox and Rush — conservatives have agreed that it’s best not to alert the base to the fact that their leaders have crossed them.

What voters want is a guarantee, at minimum, that American jobs are not put into competition with workers whose wages are kept low because they lack the freedom to improve their conditions. Colombia — with 50 union members assassinated every year — is the most dangerous country in the world for workplace activists. These murders are rarely prosecuted, and the ruling party has a long history of collaboration in the violence; one-third of the last Colombian Congress was charged with ties to right-wing paramilitaries. Signing a treaty with Colombia means putting American jobs in competition with people who fear for their lives if they call for better wages.

What voters want is a guarantee, at minimum, that American jobs are not put into competition with workers whose wages are kept low because they lack the freedom to improve their conditions. Colombia — with 50 union members assassinated every year — is the most dangerous country in the world for workplace activists. These murders are rarely prosecuted, and the ruling party has a long history of collaboration in the violence; one-third of the last Colombian Congress was charged with ties to right-wing paramilitaries. Signing a treaty with Colombia means putting American jobs in competition with people who fear for their lives if they call for better wages.

As a candidate, Sen. Obama opposed the Colombia treaty “because the violence against unions in Colombia would make a mockery of the very labor protections that we have insisted [on].” The violence is not better now than in 2008. But President Obama now supports the treaty — ostensibly because the Colombian government has promised to do better in the future.

No business would sign a contract based solely on good intentions, with no enforcement mechanism. But these are the terms the president signed, and that Speaker Boehner can’t wait to ratify.

Any treaty with Colombia first requires proof that conditions on the ground have truly changed. That’s why the labor movement called for three years with no assassinations (a standard almost every other country meets) before the treaty can be ratified. We also need guarantees that promises are kept. Guatemala famously ended the murder of unionists for the two years before Congress ratified the Central American Free Trade Treaty. Afterward, protecting union members no longer mattered, and murder rates rebounded. The EU’s treaty with Colombia includes unilateral suspension of benefits if Colombia violates fundamental human rights; but ours does not. Once Congress votes, Colombian murders can continue unabated without penalty.

For the government to sign such treaties is to play a cruel joke on the scores of Colombians whose lives remain in danger, and on the millions of Americans whose jobs are threatened by unfree labor.

Like Republicans, the White House is eager to get these treaties done quickly, so that voters will have forgotten by the fall of 2012.

To see the Obama administration and Republican leadership quietly collaborating to seal this deal in knowing violation of the voters’ will is among the most telling signs of corporate power in Washington, and among the most depressing stories in these tough times.

Lafer is a professor at the University of Oregon; in 2009-2010 he served as senior adviser to the U.S. House’s Labor Committee, where he was responsible for labor standards in international trade treaties. This column originally appeared in The Hill and is reprinted with the author’s permission.