OPINION

Boeing’s cost-cutting business model is failing

Will Boeing make great products, which generate cash flow, or will it continue being a company that generates great cash flow — and makes airplanes?

By STAN SORSCHER

(July 8, 2019) — Employees come to work to do their jobs. We aren’t usually aware of workplace culture, even over a span of years. We learn culture from co-workers and managers when they make decisions and demonstrate problem-solving skills. Leadership messages affect thousands of decisions that add up to success or failure of the organization.

For many years, Boeing competed with Airbus and other producers for airline customers based on performance of its products. As a recent news report put it, Boeing now competes for investors with Exxon and Apple.

For many years, Boeing competed with Airbus and other producers for airline customers based on performance of its products. As a recent news report put it, Boeing now competes for investors with Exxon and Apple.

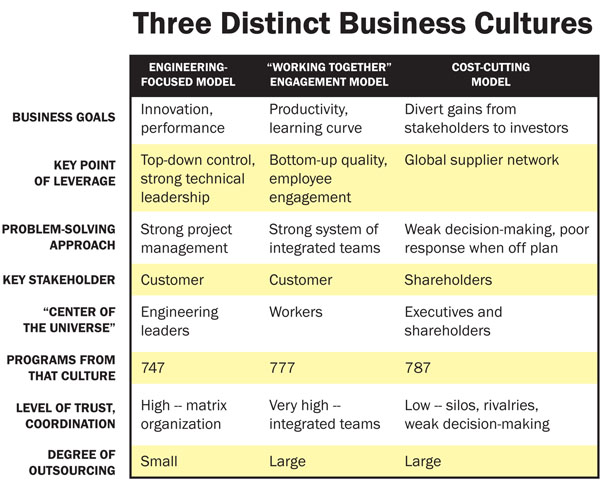

Boeing rose to the top of the airplane business as an engineering company, focused on performance of its products. Boeing made bold decisions that “bet the company” and prevailed over competitors.

In the ’90s, Boeing business culture turned to employee engagement, process improvement and productivity — adopting the “quality” business culture that made Japanese manufacturers formidable competitors.

In the late ’90s, Boeing’s business culture shifted again, putting cost-cutting and shareholder interests first.

Some business cultures are well-suited to commodity-like products but are a bad fit with performance-driven products.

Ask a financial analyst, “Are airplanes commodity-like or performance-driven?”

Business instinct is to cast the question as a market transaction. Airline customers worry about price, delivery dates, training costs, spares, maintenance and other factors, but, overall, those considerations come out very close in the end. The last major innovation in air travel was the jet engine in the 1950s. A business analyst would say the airplane business is “mature,” the products are standardized, innovation is slow, so airplanes are commodity-like.

Now ask a different question: “Are the design, development, testing and manufacture of airplanes commodity-like or performance-driven?” Whoa. Tough question.

Actually, making airplanes is performance-driven.

Success or failure of an airplane program turns on productivity. The first airplanes off the production line sell at a loss. Costs come down over time, the quicker the better. If your business model emphasizes productivity, employee engagement and process improvement, costs go down faster. This was the essence of the “quality” business model Boeing followed in the mid-’90s. The 777 had the best “learning curve” in the business.

On the other hand, if your industry is mature, and your products are commodity-like, business-school theory says a cost-cutting model is appropriate.

Wal-Mart perfected its particular version of the cost-cutting business model. Amazon adapted that model to its industry. Boeing has adapted it to high-end manufacturing. These companies are super-stakeholders with market power over their supply chains. The point of this business model is that the super-stakeholder extracts gains from the subordinate stakeholders for the short-term benefit of investors.

Wal-Mart perfected its particular version of the cost-cutting business model. Amazon adapted that model to its industry. Boeing has adapted it to high-end manufacturing. These companies are super-stakeholders with market power over their supply chains. The point of this business model is that the super-stakeholder extracts gains from the subordinate stakeholders for the short-term benefit of investors.

Subordinate stakeholders are made to feel precarious and at-risk. Each supplier should see other suppliers as rivals. Similarly, each work location should know it competes on cost with rival work locations. Each state or local government should compete for incentives against rival states.

In this model, subordinate stakeholders never say “no” to the super-stakeholder — not workers, not suppliers, not state legislatures.

This cost-cutting culture is the opposite of a culture built on productivity, innovation, safety, or quality. A high-performance work culture requires trust, coordination, strong problem-solving, open flow of information and commitment to the overall success of the program. In a high-performance culture, stakeholders may sacrifice for the good of the program, understanding that their interests are served in the long run.

In the productivity-based 777 program, it would have been career-limiting to withhold negative information from managers. They needed timely information to find a solution as far upstream as possible.

According to Boeing’s annual reports, in the last five years Boeing diverted 92% of operating cash flow to dividends and share buybacks to benefit investors. Since 1998, share buybacks have consumed $70 billion, adjusted for inflation. That could have financed several entire new airplane models, with money left over for handsome executive bonuses.

Boeing’s experience with its cost-cutting business culture is apparent. Production problems with the 787, 747-8 and now the 737 MAX have cost billions of dollars, put airline customers at risk, and tarnished decades of accumulated goodwill and brand loyalty.

Boeing’s experience with its cost-cutting business culture is apparent. Production problems with the 787, 747-8 and now the 737 MAX have cost billions of dollars, put airline customers at risk, and tarnished decades of accumulated goodwill and brand loyalty.

Stakeholders throughout the industry want our trust restored. This is a leadership moment for Boeing executives and its board of directors. Will Boeing make great products, which generate cash flow, or will it continue being a company that generates great cash flow — and makes airplanes?

Stan Sorscher is a labor representative for the Society of Professional Engineering Employees in Aerospace (SPEEA), IFPTE 2001. This opinion column originally appeared in The Seattle Times and is posted here with the author’s permission. Follow Stan Sorscher on Twitter @sorscher.

Stan Sorscher is a labor representative for the Society of Professional Engineering Employees in Aerospace (SPEEA), IFPTE 2001. This opinion column originally appeared in The Seattle Times and is posted here with the author’s permission. Follow Stan Sorscher on Twitter @sorscher.