LOCAL

How we close Native American Women’s pay gap

Apprenticeship lifts up Indigenous women and their communities

By SARAH TUCKER

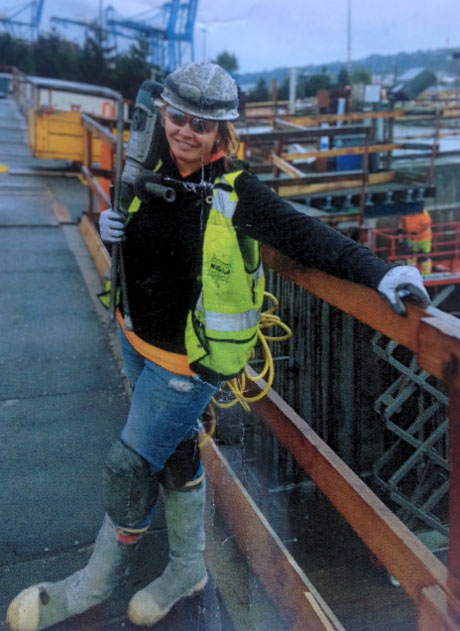

SEATTLE (Nov. 30, 2023) — At 5’-1½, Christina Riley is not the stereotypical image of a journeyman laborer. With a laugh, she’d be the first to tell you that. But not only is Riley a laborer by trade, she’s a natural organizer, an innovator who draws on her past experiences to guide her work expanding apprenticeship access for Indigenous working folks across the western U.S.

SEATTLE (Nov. 30, 2023) — At 5’-1½, Christina Riley is not the stereotypical image of a journeyman laborer. With a laugh, she’d be the first to tell you that. But not only is Riley a laborer by trade, she’s a natural organizer, an innovator who draws on her past experiences to guide her work expanding apprenticeship access for Indigenous working folks across the western U.S.

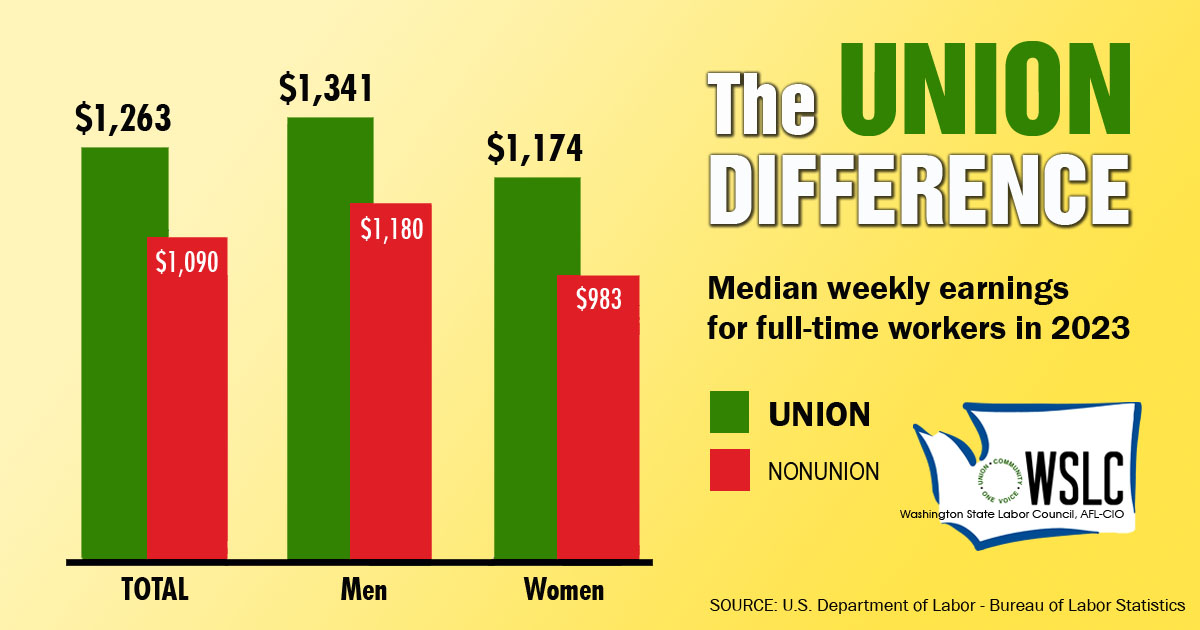

Native American women are some of the lowest paid workers in this country, averaging just 51 cents for every dollar a white man earns. Native American Women’s Equal Pay Day, observed on November 30, recognizes how far into the current year the average Indigenous woman must work to make the average white man’s wage in the year prior. Data tells us that union jobs help close wage gaps. But how do we ensure Indigenous women can access those jobs?

“You need somebody who has walked the path to say, you can do it. I did it. And here’s how,” says Riley. “That’s step one.”

“I don’t even know what that word is”

A Tlingit & Haida tribal member, Riley was born in Juneau, Alaska, like generations of her family before her. Riley’s childhood wasn’t easy; her parents were young, hadn’t graduated high school, and struggled with addiction. As a young teen, she relocated to Washington and at 16, moved out on her own. Balancing school and honor choir, she worked in a casino to support herself. At 19, armed with a GED, Riley got her flagger certificate and walked into Laborers International Union of North America (LiUNA) Local 252 looking for work. There, she heard about apprenticeship for the first time.

“I was like, ‘I don’t even know what that word is,’” said Riley. But as it was explained to her, she realized it could be a good opportunity for her, even though the apprenticeship coordinator was frank that she wasn’t a traditional applicant.

“He told me, ‘You are a terrible applicant, but I love that you’re here trying,’” laughed Riley. “And it was true! I didn’t know anything about construction. I had no idea what a laborer did, but I was selected as a Native American, 19-year-old female.”

Riley struggled through ‘hell week’, digging ditches and scaling towering scaffolding. But instructors like Chuck Moe encouraged her, and despite the odds, she passed. She went to work, mostly doing concrete and demolition, learning from the journeymen on the job with her.

“Cultural needs for success”

At the time, women were scarce on these job sites, and mentorship programs were sparse. “I had a lot of brothers, and they looked out for me,” said Riley. “They gave me the strength and confidence to be successful… Once that confidence came, man, that ceiling just kept rising.”

Riley, once an unlikely apprenticeship candidate, saw an opportunity. Despite the odds, she’d made it through. Maybe she could pull others up with her. So she applied as an apprenticeship coordinator with Northwest Laborers.

Riley, once an unlikely apprenticeship candidate, saw an opportunity. Despite the odds, she’d made it through. Maybe she could pull others up with her. So she applied as an apprenticeship coordinator with Northwest Laborers.

“I thought, ‘I’m so young, they’re never gonna hire me’,” she said with a laugh. “’This is for old men’.”

But she was hired. And from this new vantage point, Riley recognized the barriers to accessing apprenticeship that boxed out many Native Americans, barriers she had navigated around herself. As she worked more with local tribal communities, she started to think through what would break open meaningful opportunities for tribal members.

“I really learned some of our cultural needs for success,” said Riley.

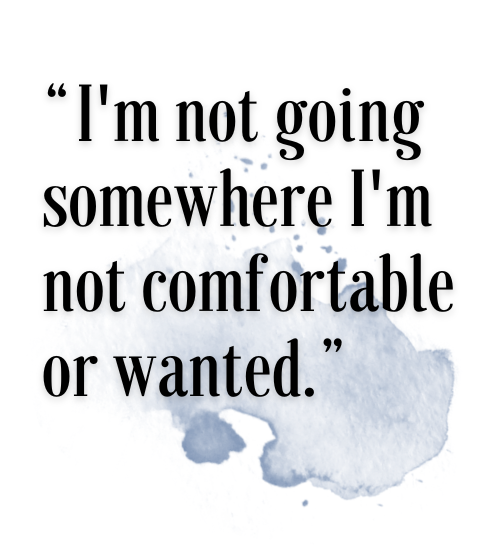

“I’m not going somewhere I’m not wanted”

It’s these cultural needs that drive Riley’s work building bridges between organized labor and tribal governments and communities. This work isn’t easy. Tribal governments – and tribal members themselves – don’t have universally positive views of organized labor, or of working outside tribal communities. This wariness is rooted in generational experience, often born out of broken trust, or isolation and discrimination on the job.

“One of the biggest barriers is mental,” said Riley. “[Folks thinking] I’m not going somewhere I’m not comfortable or wanted, so I’m gonna stay right here on our tribal land, and I’m gonna work only within our tribe.”

“One of the biggest barriers is mental,” said Riley. “[Folks thinking] I’m not going somewhere I’m not comfortable or wanted, so I’m gonna stay right here on our tribal land, and I’m gonna work only within our tribe.”

Riley is generous with her personal story because sharing her experiences, of an unsteady home life growing up, of struggling to graduate high school, working in food service at a casino – these are relatable experiences for many of the tribal members she works with. Despite the obstacles, Riley’s found success and economic security through union work. If there’s a place for her in labor, there’s a place for more Indigenous folks as well.

Riley believes in the power of apprenticeship to not just change the lives of individuals, but to break harmful generational patterns and allow folks to create new ones that uplift entire families. She’s seen this in her own life, and she’s seen this transformation in the lives of apprentices she’s worked with.

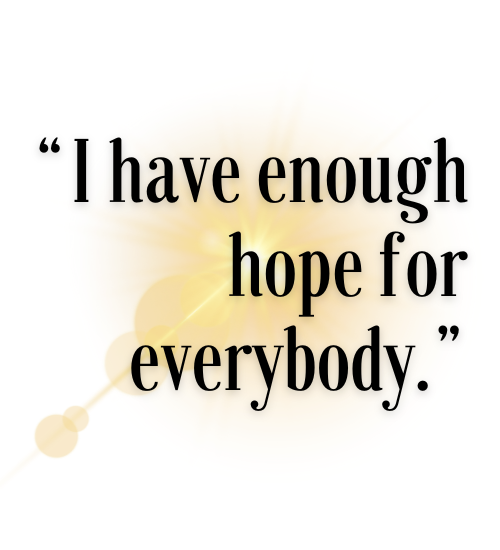

“I have enough hope for everybody”

It’s not easy work. “One day I had four tribal members come in. They had no hope, they had no goals, they had no experience. I thought, ‘this is gonna be a really rough go at it. And I’m not expecting a lot of success. But, I have enough hope for everybody.’”

It’s not easy work. “One day I had four tribal members come in. They had no hope, they had no goals, they had no experience. I thought, ‘this is gonna be a really rough go at it. And I’m not expecting a lot of success. But, I have enough hope for everybody.’”

Like many tribal members, these apprentices faced structural barriers. “All four of them did not have a high school diploma. Three of them did not have a driver’s license,” said Riley. Without outreach that responds to these needs, “the door is already shut.”

With Riley’s support, three of the four made it through. And one of those apprentices, Nancy – who pushed her fellow apprentices to put in the work – is now featured on LiUNA billboards, a beautiful, powerful example of what apprenticeship can do. “Now we have a whole life changed,” said Riley. “A generation that is standing on its own two feet and teaching her children the value of her union.”

“You can’t build without understanding”

In 2021, Riley took the lessons she’d learned at LiUNA and opened her own consultancy, working directly with tribes and unions. Based in Washington state, Riley works with tribal communities and unions in the Pacific Northwest. Her model is incredibly successful, focusing on intentional relationship building between tribal communities & unions, respect for tribal government, and support services for apprentices.

That success requires buy-in. More and more unions are intentionally working with tribal communities, including the Operating Engineers, Painters, Laborers, Machinists and Carpenters, all invested in building relationships.

That success requires buy-in. More and more unions are intentionally working with tribal communities, including the Operating Engineers, Painters, Laborers, Machinists and Carpenters, all invested in building relationships.

These relationships take time to build, especially to establish trust, often after years without it.

But understanding and respecting tribal dynamics is essential. “Most people have no idea of the tribal government and the tribal government authority,” said Riley. “It’s a huge education piece.”

When partners engage with one another in good faith, the results can be game changing. Take the work in partnership with the Puyallup. Tribal construction projects along the I-5 corridor have brought hundreds of jobs to the region in the past decade. Historically speaking, these projects have sometimes brought tension.

“Union partners were not doing a good job of building relationships with the tribes at the time,” said Riley. “And the tribes were doing a good job of saying, we are sovereign land. Get the heck out of here.”

But patterns can be disrupted. And that’s exactly what Riley and others helped to do on these projects; repair trust, build new relationships, and offer avenues for shared success.

The results speak for themselves. Millions of dollars of construction work was completed by union workers, with high standards for pay and safety. And through the project, Many tribal members were familiarized with the concept of apprenticeship, often becoming apprentices, not only working on these tribal construction projects, but going on to work on other projects as apprentices and ultimately journeymen. More Native workers joined the labor movement. More union members, Indigenous and otherwise, saw the opportunities that come from intentional outreach.

In the time Riley has been doing this work, she’s seen dramatic changes.

“Now, many apprenticeships have language in their selection process for tribal members working through a tribal employment rights office,” said Riley. “[Tribal members] don’t have to have their driver’s license, they don’t have to have their high school diploma or GED to get started. The goal is that they’ll reach that as they’re working through the apprenticeship program.”

Tribal governments and communities are engaged to support members working through apprenticeship programs, and there’s greater understanding in organized labor about the systemic challenges Native American workers face. Mentorship is now a common part of the apprenticeship conversation, far different from the days when Riley was the sole woman on a job site.

And that mentorship and community building is deeply necessary for workers’ wellbeing. Riley notes that suicide remains a leading cause of death for trades workers, and is so pervasive that many unions have developed programs to support workers struggling.

Suicide is also a leading cause of death for Native Americans, particularly young women. “Especially where I’m from, suicide is common,” said Riley. “It is a huge problem. And through Covid we’ve only seen that become more staggering.”

Working together to support their people, unions and tribes have developed common ground. Said Riley, “you see the unions saying, whatever we have, we offer to you. If you want it, you got it. These resources are yours.”

Riley is eager to see the work she does implemented more broadly, and with institutional support. She points north as an example, where there is a Canadian government-run Indigenous board dedicated to ensuring outreach to tribal communities about registered apprenticeships. “That means it’s somebody’s job to make sure that registered apprenticeship is being offered to our tribes,” said Riley. “Not as a transaction, but a requirement.”

“You can disagree and still have a meaningful relationship”

The appetite for this work is growing, with more and more unions recognizing the opportunities this targeted outreach produces. Still, disagreements can crop up. But for Riley, a strong relationship is one that can weather conflict. “Sometimes labor and tribal governments do not agree, and a lot of times [the disagreement] is projects. So navigating that [requires] understanding that you can disagree and still have a meaningful relationship.”

Of all the lessons to be gained from Riley’s work, perhaps this is the most important. Even with shared goals, disagreements still happen. But investing in our people and investing in genuine relationships means we can navigate conflict without breaking our solidarity with one another.

Solidarity is the core of organized labor, it’s what builds community bonds between working people. That community was pivotal for Riley, and she recognizes it as essential for Native American workers in our movement. As Riley puts it, unions can “empower the worker to see what is in front of them and utilize it.”

With that empowerment comes confidence. “We can all claim our place,” said Riley. “We just have to be able to see ourselves there.”

You can learn more about Christina Riley’s work at consultingbychristina.com.